A Commonsense Look at the Proposed Sale of Public Lands—And What It Means for the Sierra We Call Home

By Charlie Pankey | Sierra Rec Magazine

I’ve pulled off the side of the road just north of Truckee more times than I can count.

Sometimes it’s for a spontaneous hike at Prosser Hill. Other times, it’s to catch the last light hitting Boca Reservoir or to find a stretch of dirt road where I can hear nothing but the wind and my own breath while enjoying the wildflowers. These places don’t come with interpretive signs or visitor centers. They don’t show up in glossy travel brochures. But they matter. They are places that i hope to share with my grandchildren and they with theirs.

And if a new proposal in the U.S. Senate becomes law, places like these—quiet, unsung, deeply personal slices of public land—could be sold off without you or me ever getting a chance to weigh in. Sound oddly similar to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed by President Andrew Jackson.

What the Bill Proposes (And Why It Hits Different This Time)

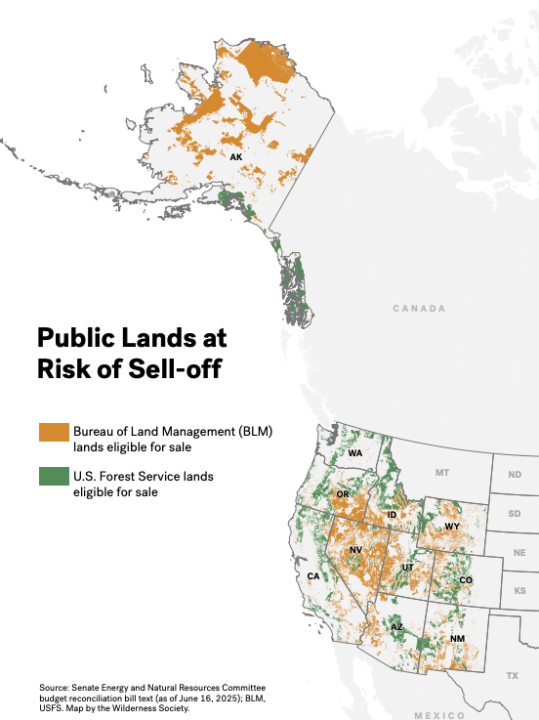

A provision in the current Senate budget reconciliation package requires the sale of 2 to 3 million acres of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service. The goal is to raise money for housing, tax relief, and infrastructure—but the mechanism is blunt: any parcel that meets a broad eligibility standard is fair game.

It’s not about Yosemite or Lake Tahoe. Not directly. It’s about the connective tissue in between—the land where people hunt, fish, trail run, train their dogs, ride bikes, or escape for a night under the stars without needing a permit or a reservation.

The proposal allows the federal government to sell these lands over the next five years—quickly, and quietly.

And here’s the part that sticks with me:

There’s no formal requirement for public input. They just want to take it in the voice of progress and growth.

“You May Only Find Out When You See a ‘No Trespassing’ Sign”

The bill does include a requirement to consult with local governments, governors, and Tribes. But it skips a step that makes public land public: the right of the people to speak up before it’s taken away.

Right now, identifying lands for disposal involves a transparent, public process (Now personally this process could use a review in itself)—but this bill would erase that. Land management agencies must publicize the parcels they nominate, but if a private interest nominates a parcel? That doesn’t have to be shared.

Even the final sale doesn’t need to be disclosed. Agencies wouldn’t be required to announce which parcels were sold, or who bought them.

As one policy researcher put it:

“Instead, the public may only find out when they show up and see ‘no trespassing’ signs.”

That line haunts me. Because I know exactly where that could happen.

Picture This in the Sierra

In Truckee

There’s a fire road behind Boca Reservoir that most maps won’t name. If you’ve driven it, you know the sound your tires make on the gravel and the smell of pine sap when the sun’s been out for a while. These aren’t official campsites. No one’s charging a fee. But if you grew up in this part of the Sierra, or came here enough, you might know this is where your kid took their first cast or where your friends brought beers after a ride.

Now imagine that road gated. A sign posted. “No Trespassing.” No warning. Just gone.

These are the kinds of public lands that qualify under this new proposal—not the iconic places you see on postcards, but the ones you live with, quietly, until they’re taken away.

Outside Reno

Peavine Mountain doesn’t ask much of you. It’s just there—an outline on the horizon when you’re driving I-80 west, or a snow-dusted ridge above Spanish Springs when the weather turns. BLM lands sprawl across its lower slopes, stitched together by old mining roads, now claimed by trail runners, dirt bikers, and dog walkers and wild horses trying to make it home before sunset.

But convenience is a double-edged sword. These lands are close to cities. Developable. Easy to nominate under a bill that prioritizes accessibility over value. The kind of place a private buyer could fence off and flip before the community even notices.

Around Mammoth Lakes & Long Valley

Drive south out of Mammoth, past the resort traffic and second homes, and the land opens up—wide and volcanic, scarred by time and tectonics. This is Long Valley. Hot Creek bubbles quietly on cold mornings. The gravel roads wind past Crowley Lake, between soft ridgelines that roll out toward Glass Mountain. There’s no entry kiosk. No ranger. But this is where people go when they want to feel small and free and anonymous again.

It’s also where the maps show huge swaths of BLM land, not protected by wilderness or park designations—just open, for now. This bill wouldn’t protect it. In fact, it might fast-track it for sale. No notice. No signage. Just one day—gone. A new fence. A new rule.

In the Backwoods of Quincy

North of town, where the Plumas pines grow tall and quiet, the forest folds in on itself. Bucks Lake. Meadow Valley. La Porte Road in winter, after the snow has settled and the plows stop just short of the best part. Families have been coming to these woods for generations—not for Instagram or itineraries, but because they belong here, in a quiet way. They know where the deer migrate in October. Where the fish hold under the cutbanks. Where a snowmobile can glide across an old logging route without bothering a soul.

It’s not protected by a signpost or a monument designation. It doesn’t need to be. Or at least, it didn’t.

Until now.

Because if this bill passes, and no one asks which lands are worth keeping, then no one will stop when the wrong ones go up for sale. And we’ll find out not by press release—but by the gate that wasn’t there yesterday.

This Isn’t Alarmism. It’s Reality.

Some readers may say: “That’ll never happen.” That the number—2 to 3 million acres—is small in the scheme of things.

And yes, it is a fraction. But the criteria? Wide open. The process? Opaque. The precedent? Dangerous.

We don’t need to exaggerate to be concerned. We just need to ask:

Why is something this permanent being done without a transparent, public process?

A Commonsense Question: What’s the Rush?

Most Sierra Rec readers aren’t out here waving protest signs. But we do care about what’s being done in our name—especially when it involves places that have defined our weekends, our memories, and in many ways, our identity.

If the goal is to support affordable housing, why not first evaluate federal lands already designated for urban development or surplus use? Why not make a public plan and request in regions, cities and communities that are bursting and need help with growth? Keep it targeted and with clear and clean goals for that specific local region.

If grazing lands are on the table, how will that affect the working families that rely on them? If recreational lands are included, what’s the long-term cost to communities that depend on outdoor tourism? In Nevada, what’s it mean for our Wild horses, more helicopters and dangerous round ups?

We don’t have to fight every acre to care about how the decision is made.

What You Can Do (Even If You Hate Politics)

- Read the bill. Ask hard questions. Share facts, not fear.

- Contact your Senators and let them know if you think public input should be required.

- Talk to your community. Ask your local officials what’s at risk in your area. Push for transparency—at the very least.

This isn’t about left or right. This is about access, accountability, and the places we love.

I’m not here to be political. I’m here because I’ve stood in too many quiet spots in the Sierra where the wind carries more meaning than words. And I can’t help but wonder what we’d lose—not just in land, but in connection—if those places quietly disappeared.

We’ll be covering this more on the Sierra Rec Now Podcast next week. If you’ve got questions, or stories about places you’d hate to see sold, send them our way.

Let’s have the conversation—before the signs go up.

#DiscoverMoreSierra | #PublicLandsMatter | #SierraRecMagazine